What?

There are two major points made in Chapter Four of How Learning Works (HWL). Mastery is an important final stage of learning that requires specific teaching practices to ensure student achievement, and mastery as an instructor can leave us blind to the challenges students face on their own road to this goal.

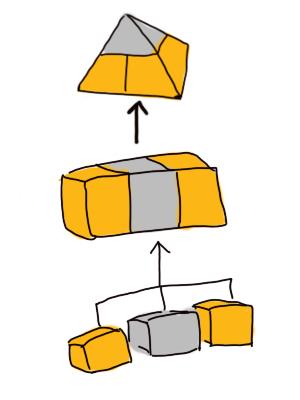

HWL offers a four-stage model for progression towards mastery:

- unconscious incompetence

- conscious incompetence

- conscious competence

- unconscious competence

and three teaching modes for their attainment:

- component skills

- integration

- application

Application will be familiar to many instructors as the ‘transfer’ learning that we hope to see when students are able to apply concepts or skills learned in one context (typically, the classroom or lab) to a new context (hopefully, the real world).

This topic lends itself to both traditional academic disciplines and to trades and skill-based learning. Examples can be developed from both spheres, but perhaps there are differences in how this plays out in each context.

The implication for mastery in instructors is that having achieved the ‘unconscious competence’ stage, instructors have blind spots where they don’t realize that internalized steps or an intuitive ability to apply knowledge is perceived by learners as a black box, or not perceived at all. Options to alleviate this perceptual mismatch are offered in the “Strategies to Expose and Reinforce Component Skills” section of the chapter.

So What?

This chapter makes a strong case that supporting the path towards mastery is the key to deeper learning. An argument could be made that the ‘application’ stage is where professional fields like accounting, or general skills like critical thinking, make our graduates successful in their lives after graduation.

Now What?

As you think about this chapter, consider how it relates to your own teaching practice or the learning you have supported.

- Are these stages of learner achievement and the teaching modes that support their attainment, factors in your context? Where does the model fit and does it fall short in some aspect?

- If you have one, describe your own experience with a ‘blind spot’ as an instructor. How did you overcome it?

To encourage participation, those who share a comment/post this week will have their name entered into the Chapter Four draw for a $25 CAD gift certificate for Chapters Indigo. Read the contest guidelines here. Good luck!

The Book Club chat on Chapter Four will take place on Friday, Oct 12th at 10 AM PST. Check out the schedule and how to connect with the group. We also invite you to say hello in the Comments section of our Intro post.

This model fits very well in my context, and not just because the authors use physics examples explicitly in the test. My challenge as an first year instructor is to help the students make that huge step from secondary school to college/university where the expectations are for much more integrated problem solving. I was tickled pink to read about “scaffolding” and the “worked-example effect” as I now have a word for what it is that I do in class. It is always nice to get some external affirmation.

My blind-spot as an instructor is needing to have patience for how long it takes students to solve what (for me) is an elementary math problems. How I overcome this is by using a clock. I set up a problem and when I say “I will give you a minute” I give then the 60 seconds without talking or hinting. Or if I do talk, then I give them more time. It is agony for me at times to not talk, give hints, “help” them along, but I know they need that time. I walk around the room and make sure that the vast majority of the class has finished that part before going on. This has taken me years to get to that stage. I have notes in my in class work as to how much time to give them.

On a related note, a sort of second blind spot, is that I use on-line quizzes in Blackboard (Douglas College’s on-line-course space) and I give them 10 chances to do the quiz. I have what I consider elementary math practise ones at the start of the year to help them self-diagnosis. I talk and write emails to those small percentage of students who are clearly having trouble with basic math. (Sigh… it does not always work. Next week is mid term week and I know that 3 of my 36 students are in for a big shock when they get their marked tests back.) And building on that, in the more advanced online quizzes is I make a point to do three questions — the first that is a straightforward plug and chug of the basic concept that they “should” have been doing for two or more years, a medium hard one that is similar to what they would have had in the previous year and then one at the level that they are expected to do in this course. It gives them some confidence. I am still amazed at how many students ask for help with the third one and when I ask how did they do on the first two and they will reply that “I did not bother with those.” Sigh. Can you tell I am deep in mid-term angst?

When I started teaching an established teacher gave me great advice about writing tests. He said that if it takes you 10 minutes, it will take then 30. That ratio has changed slightly over the years as I get more and more practise, but the concept has stayed with me.

Overcoming my blind spots was helped by me reading Norman’s Doidge boos “The Brain that Changes Itself” that showed how our brain cells literally grow together with practise. I chant to myself that the students have not changed that much over the decades, but that I have.

Hi Jennifer,

This is an interesting set of observations about mastery. By some coincidence my daughter is taking first year physics (for non-physics majors) at UVic this semester and, as she’s been deeper into chem, bio and math, this is the topic where she lacks mastery. The interesting thing was that she knew the processes to solve the problem, but she didn’t know how to resolve the word problem into the principles/steps. I was able talk her through the problem (though my last physics class was in 1981) but I couldn’t tell her which bits of trig to use for the solution.

One thing that most LMSs will do for you is to make access to one quiz contingent on success in a prior quiz. You could generate a set of practice questions that forced students to master questions at one level before progressing. This sort of thing takes a lot of initial work but should be durable and easily shareable.

Thanks for providing such a clear summary Keith. I like the “What?” “So What?” “Now What” structure. This chapter made me think of the research I read about years ago (2000) in How People Learn, a National Academies publication that reviewed a wide collection of education research – do you know it? One of the things they said when they talked about the different ways that experts and novices think is that teachers can help learners by making their thinking explicit. I’ve always tried to do that, where it fits as it is not always possible for learners to see the connections I’m making without more time, learning and practice. I rely a fair bit on organizers – sometimes advance organizers, sometimes visuals or models that I loop back to again and again. Some learners seem to appreciate having a structure to hang their learning on; others just ignore it but benefit from it after mucking about in the new knowledge and activities. I’ve tried my very rough version of sketch noting to illustrate my thinking, tried audio and video podcasts, practice different ways of writing, etc. I’ve found that it seems easier to help students make connections, recognize patterns, link what they’re learning to larger concepts or related contexts when I’m teaching online. The ability for learners to go back and check what I said before, or revisit an example or a model and look through the discussion that surrounds an important concept or task – I think it makes it easier for students to develop their personal reflective and analytical skills. Plus, it benefits me as the instructor to be able to review their individual contributions, look for absence of participation or indications of confusion and connect directly with each student.

I struggle with an instinctive dislike of the term “mastery” as it seems to present a static view of learning (IMHO); as you mention in your overview, it does seem more relevant in a “hard” science” or practical trade.

I’ve found that I often feel that I have too little time with learners (either because of all the demands on adult learners who are often juggling many different classes, work and life demands or because of the structure of a course) to really help them make important connections and develop the ability to apply skills well in a variety of contexts.

Cheers…

Hi Sylvia,

Thanks for your thoughtful post. I’ve been thinking about the term “Mastery” as well and what discipline areas it really aligns with more than others. We had a really great discussion today and Robynne tweeted some great points made in the discussion. The “What? So What? Now What?” format is from Liberating Structures (liberatingstructures.com). I’m playing with different ways we can use them for teaching and learning 😉

L

Delighted to announce the winner of the Chapters Indigo gift card draw prize is Jennifer Kirkey! Congrats Jen! We’ll be in touch!

L