Can you recall…and predict?

1. Think about the principles related to retrieval practice introduced in Chapter 1. Which principles might you expect to transfer to Chapter 5 – Practicing?

2. Can you recall the differences between massed and spaced practice (Chapter 3, Interleaving)? Which type of practice might you expect to see emphasized in Chapter 5 – Practicing?

BIG IDEA(s): Identify the cognitive skills that are integral to the learning activities you assess for grades and make sure to allow time for students to practice them, in class. Encourage students to “…engage in active, mindful practice of important intellectual skills” throughout the course.

Lang begins his discussion of practicing with a cringe-worthy example drawn from a 2007 course in contemporary British literature. Despite his preparation (sharing tips on effective presentation techniques, exhorting students to practice, and helping some students with the structure and organization of their material), he was astounded by how poorly the students performed. His assumptions about their recognition of the importance of rehearsal and their basic presentation skills were proven painfully wrong.

via GIFER

After reflection, Lang hypothesized that small, facilitated practice of cognitive communication skills (that were part of his graded activities) would help students perform successfully. He recognized that he needed to revisit his assessments to clearly identify the skills that he had assumed that students would know or could “figure out” to complete graded assignments.

His small teaching strategy (the first Big Idea) involves the recognition and analysis of the cognitive skills that are required to successfully demonstrate learning in our graded assignments / activities. We need to be explicit about the cognitive skills we value (review the skills listed for “Understand” in Blooms updated Taxonomy), and to plan ways to offer structured, manageable opportunities to enable students to practice BEFORE we ask them to completed assessed, graded demonstrations of their learning.

In Theory

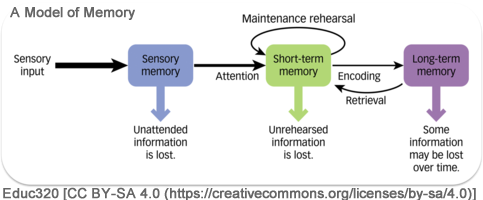

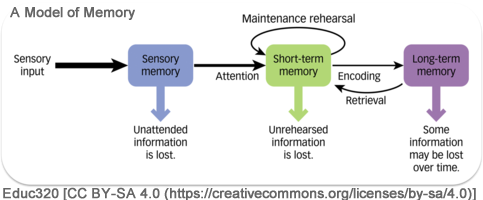

Lang introduces the value of guided practice in his example of improving his skiing skills with the observation and feedback of a more knowledgeable skier. He emphasizes the importance of rehearsal and practice of skills in academic learning – the practice should ideally take place in class, with the observation and feedback of a knowledgeable instructor. To help us understand the role of consistent practice in improving students’ cognitive skills, he reviews the potential bottleneck that our limited short-term (or working) memory imposes as we struggle to combine new information from our immediate environments while trying to access deeper, longer-term memories.

Lang also cites Daniel Willingham’s perspective on the value of extensive practice to develop “cognitive proficiency.” By providing opportunities for students to practice and be able to use some lower level cognitive skills automatically, they can integrate higher level cognitive skills as needed.

Providing instructor-guided, in-class practice is, at least partly, to avoid the risk of students practicing without thinking, or practicing incorrectly. An additional risk, according to Ellen Langer, is that students may practice it to the point of “overlearning”, which she believes will prevent them from getting better at thinking mindfully. Langer identifies the three main characteristics of mindful learning as:

- Flexibility – ability to create new categories or shift strategies during learning

- Openness – to new approaches that may benefit understanding or application of skills

- Multiple perspectives – ability to recognize the potential value of alternative perspectives

With the availability of timely feedback and support from an instructor, there is greater likelihood that students can master the supporting skills required to allow them to observe their own practice, to be open to new ways of doing things and to think deeply – to think “mindfully.” This is Lang’s second Big Idea.

I’ve suggested this as a 2nd Big Idea because it seems to embody thinking that involves the affective domain as well as the cognitive domain. To scaffold student learning of these broader, deeper skills may require a more significant re-appraisal of our teaching and course design and delivery than we might first understand from Lang’s examples.

Models

- Unpack Your Assessments

Take time to analyze your individual assignments (especially those that contribute to the grading) and your overall assessment strategy. Does your distribution of marks and types of assignments indicate that you value some cognitive skills more than others? Do you currently provide practice opportunities and explicit feedback to develop these skills in your students?

Do you provide rubrics or marking outlines to make cognitive skills explicit for students?

- Parcel Them Out and Practice Them

Break down (parcel out) the cognitive skills required for important assignments. Find opportunities for “stepped” practice so that students can take on manageable chunks of new skills and develop them over the time of the course.

By looking ahead in the syllabus, you can schedule practice opportunities at strategic times that support the required demonstration of learning (and use of important cognitive skills) on a specific date.

Lang suggests that the last 10-15 minutes of class are the best times to provide practice opportunities. These opportunities could include a brief (5 min) teacher-led review of the important elements of the cognitive skills you want them to develop, with the remaining 10 minutes used by the students to practice those skills.

- Provide Feedback

Lang suggests we combine individual and group feedback while students are engaged in practice activities in class. Be clear about how you will provide feedback to prevent students from feeling singled out. Take time to develop methods that will ensure you balance your observations, attention and feedback so that students receive equitable access to your expertise.

Principles

To promote mindful learning in our classes, Lang suggests the following:

Make Time for In-Class (Scaffolded?) Practice

Lang is focused on the importance of direct teacher observation and timely feedback to prevent “overlearning” or the development of poor habits during practice. I’d suggest the use of a term like “scaffolding” to recognize that in-class observation and feedback isn’t always possible nor is it always the best way to prevent these problems. There are various ways to provide individualized observation and feedback beyond practice sessions in large groups facilitated by the instructor. Integrating specific practice opportunities that involve the use of technologies to record and share student(s) practice sessions with the instructor and/or other members of their class might provide additional value and equity in learning.

Space It Out

The importance of layering and spacing out the types and times of cognitive skills practice opportunities is emphasized throughout this chapter and builds on the previous research shared on the value of interleaving and spaced practice.

Practice Mindfully

Lang began this chapter with examples of the value of practicing easily recognizable cognitive and psychomotor skills. He introduced the deeper, broader learning inherent in Langer’s concept of mindful learning and the importance of ensuring that all practice opportunities we provide students also encourage flexible, intelligent thinking beyond the immediate demonstration of skills.

Small teaching ideas

- Before the course begins, develop a list of cognitive skills you believe students “need to succeed” (in your course or in the program they are enrolled in).

- Set priorities – which skills do student need to develop immediately? Which skills can only be developed after foundational skills are learned?

- Review the course schedule and determine where to make space for small practice sessions. For practice sessions of key skills prior to an assessment, mark the dates on a shared calendar or schedule.

- Stick to your plan. Make sure that students have multiple opportunities to practice the skills they need to do well in your course.

A few questions:

- Lang is very concerned that guided practice take place in the presence of an instructor to avoid “overlearning” or other bad habits. Do you believe this is necessary for all types of students, subjects, types of courses?

If yes, think of ways you could re-arrange your teaching practice to enable this? How many small practice sessions could you foresee in your next course?

If no, suggest ways you would adjust your provision of practice with timely feedback to develop cognitive skills in your classes.

- In Chapter 5, Lang shares stories of providing presentation skills practice in-class, with feedback from the instructor. Other educational institutions, like UBC or Vancouver Island University, provide web pages with videos and other resources or non-credit short courses, to help students build their own skills. What do you think of the potential value of these alternatives to in-class practice?

- Do you currently recognize and explicitly communicate cognitive learning skills in your classes? How?

- Are you able to assign marks for different levels of accomplishment in demonstration of cognitive skills that are valued in your assignments for grades?

References

Langer, E. (1997?) (2007?). The Power of Mindful Learning. Cambridge, MA: DaCapo

Miller, M. (2014). Minds online: Teaching effectively with technology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Willingham, D. (2014). Why don’t students like school? A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

More to read

Young, S.H. (2014, August). Seven Principles of Learning Better From Cognitive Science, Retrieved from https://www.scotthyoung.com/blog/2014/08/10/7-principles-learn-better-science/