What is the Principle?

Prior knowledge can help or hinder learning.

In Chapter One of How Learning Works: 7 Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching (HLW), the authors delve into a look at the prior knowledge of learners and how it impacts learning. Prior knowledge (PK) can be a good foundation for building new knowledge, but research shows that student learning is influenced by the nature of the prior knowledge. Depending on a number of conditions, prior knowledge can help or hinder learning.

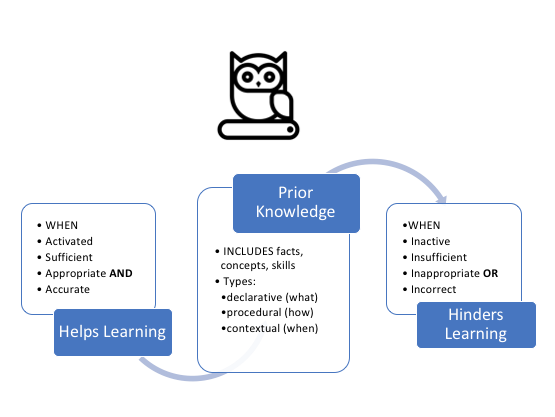

This diagram (re-created and adapted from the original in the book, Figure 1.1) shows the conditions for when prior knowledge helps or hinders learning.

Prior knowledge (PK) helps learning when it is activated. In addition, that PK needs to be sufficient, appropriate and, above all, correct.

Prior knowledge (PK) that is problematic or that hinders learning is one or more of the following:

- Inaccurate: Some deeply held misconceptions are difficult to correct.

- Insufficient: There are many kinds of knowledge such as declarative (what) , procedural (how), contextual (when) knowledge. Students’ PK may have gaps.

- Inappropriate: Correct but used at wrong time or context.

- Incorrect: Knowledge that is wrong.

So What? (What does this mean for how we teach? What does this mean for helping students learn?)

Many of us use techniques to bridge, integrate, and activate learners’ prior knowledge with the new content we are teaching. But have we considered more closely, the nature of their prior knowledge and whether it is sufficient, appropriate, as well as, accurate?

The HLW authors offer a variety of strategies in Chapter One to help us identify possible problem areas in learners’ prior knowledge and how to proactively address them. Some of these strategies include student self-assessment questions, looking for patterns of error, identifying discipline-specific conventions for our learners, or having them conduct and test predictions based on what they currently know.

Now What? (Applying the Prior knowledge principle to our practice.)

Take a moment to reflect on your current teaching practice. Is there a common misconception about the subject you teach? Share what that is and a strategy you use (or plan to use) to address this issue. To do this, simply subscribe to this blog and post in the Chapter One Comments. Alternatively, you may share your thoughts using social media with the hashtag #BookClubBC.

To encourage participation, those who share a comment/post this week will have their name entered into the Chapter One draw for a $25 CAD gift certificate for Chapters Indigo. Read the contest guidelines here. Good luck!

The Book Club chat on Chapter One will take place on Friday, September 14th at 10 AM PST. Check out the schedule and how to connect with the group. We also invite you to say hello in the Comments section of our Intro post.

Looking forward to reading together and meeting you online!

Acknowledgments

Graphics:

Owl by Oksana Latysheva from the Noun Project

Suitcase from the HLW graphic by Giulia Forsythe

I teach physics and one of the ways I address this is by doing as many “surprising” hands on things in class. One common misconception is that heavy things fall faster than lighter things. Galileo showed this was wrong more than 400 years ago, but it is an ingrained PK. I give them enough modelling clay to make a “big thing” and a “small thing” and have them drop it. the looks of astonishment on many of their faces, including first year engineers, shows that this is a needed exercise. I make it more memorable by calling these activities ‘how to amuse your friends and maybe make some money with bar bets”. Demonstrating helps, though there is scholarly research that shows demonstrations do not always work – they need to do it themselves. A class set of clay costs very little and is well worth it.

Hi Jennifer, This is sounds like a fun and effective way for your students (and you) to check what they think they know…This is a long-held misconception. I’ve got to go find me some modelling clay.

PS I’m entering your name in for the draw prize,

I mentioned the scholarly research that shows watching a demo is WORSE than not watching a demo. It was first done by Eric Mazur of Harvard, who started Peer Instruction and Clickers. Here is a nice summary. Preconceptions can be so strong that students mis-remember a demonstration. In other words they will report that the heavier thing fell faster than a light thing – even though that is not what happened. https://computinged.wordpress.com/2011/08/17/eric-mazurs-keynote-at-icer-2011-observing-demos-hurts-learning-and-confusion-is-a-sign-of-understanding/

One common misconception in my field of emergency management is that “one size fits all” in terms of how we prepare, respond and recover from emergencies. When I train, I take time to find out about the community I am in and encourage discussion of how they can implement a concept in their community to deal with a specific situation they have identified. This gives opportunity to integrate theory and practice and share best practices.

Hi Sybille,

It’s great to address this misconception in your field at the start.

Is there an activity or something you do with your students to get across to them why a “one size fits all” approach in emergency management doesn’t work?

Thanks for sharing! I’ll enter your name in for the draw.

Leva

As a freshman composition instructor I often hear early in the semester from students that they are “just not a good writer.” This often seems to stem from the belief that it is some kind of in-born talent. Often their previous experiences with writing feed into this type of inaccurate prior knowledge, which has often been reinforced for a number of years. To address this I have them explore the writing process. I start by explaining that it was once the belief that some people are just better writers than others, but that eventually someone proposed that maybe strong writers are not born but that they become strong writers by having a process. Then in small groups, I have them look up the common steps associated with the writing process and create an analogy: “The writing process is like __________.” They have to think about an activity that involves a process leading to a product and create a poster illustrating that process. This activity helps them see that there are actually a series of things they can do to improve their writing and it also helps feed into a discussion about the writing process not being a linear one but a recursive one with opportunities for reflection and improvement along the way.

Hello Becky,

What a great strategy for addressing the misconception that writing well is an “in-born talent”. By getting the students to understand the writing process, I see how you are leading them to self-discover how good writers can be made: that they can improve their craft by working at it. Thanks for sharing. (I’ll be entering your name in our draw.) We hope you’ll join our chat on Friday.

Leva

Thank you for the cool idea! Many of my students also hold this misconception, and I like this way of addressing it. I am curious to hear about some of the analogies students have come up with.

The analogies vary quite a bit, but there are some common themes that I see: baking/cooking (pizza, cakes, hamburgers, to name a few), morning getting ready routines, designing/building a house, planning a vacation. I also instruct them to not provide a list but to represent their analogy graphically/visually. Most groups do some type of flow chart but I’ve also had students create a comic strip type representation (I encourage them that “stick people” are fine). I provide multicolored markers and poster paper and usually conclude with a “gallery walk” for them to admire the work of the entire class. I then follow up by picking an example that is the easiest to convert to a recursive process, sometimes adding two-way arrows, to talk about when/why you might return to a previous “step” in the process.

Most of my work involves working with faculty (often 1 on 1 or in small groups) and my expertise lies in using educational technology to support their teaching and student learning. I often come across the misconception that many faculty believe that they are “not good with technology” and that students “are good with technology”. Educational technology use is far different than using Facebook or playing video games; so students may not be as efficient at using edtech as instructors think they are. The attitudes may be different; but that’s another conversation.

One of my strategies for working with faculty who are afraid or say they aren’t good with tech is to really listen to their needs and challenges and when I can find a technology solution that really makes sense – I start there. Just like students who are motivated to learn because of a goal; faculty who are motivated to use a technology that provides a solution to a T&L gap or increase efficiency suddenly find that they are having fun and the results can be quite rewarding. Success breeds confidence and soon their fear of learning or innovating with technology is replaced with enthusiasm about the possiblities.

Hi Janine, I like what you suggest as an effective way to address your particular PK issue (faculty fear of learning to use technology) by shifting your focus on the teaching and learning challenge and how the technology could be used to help provide a solution. The teaching and learning drives the use of the tech, as it should!

L

I definitely find the same belief among many of our faculty here – several faculty I have talked to say that they don’t talk about D2L with their students “because the students already know how to use technology/D2L”. I think a few of them had their eyes opened this fall when I ran some student orientations for our D2L and the faculty members were able to see first-hand how nervous students were about having to use D2L for their courses. I think it helped them to see students with the same reticence to using technology that they have expressed.

I’m a sucker for gift certificates to book stores (!). One of the things I teach is instructional skills to faculty members. One of the misconceptions is that incorporating active learning is difficult and time consuming. It can be both…but not necessarily so. One of the strategies I use, related to prior knowledge, is to ‘uncover’ or inquire into learners’s (ie, in my case the learners are instructors) beliefs about active learning (asking them what it is, what it consists of, why they might do it/not do it). I think sometimes people come to our T&L centres and worry that we’re all about drinking the coolaid (ie that we’ll be pushing certain approaches on them)…

Welcome Isabeau,

Exploring the learners’ beliefs about active learning is in itself “active learning”… Clever! 😉

So glad you are able to join in the Book Club. Your name is duly noted for the prize draw.

I work in the field of Early Childhood Education and Care; this semester I am teaching an introductory Child Development course. A common challenge that I experience is the ‘image’ that students hold, when they think about very young children. They often view them as somehow lacking and/or passive – without voice or contribution – waiting for the Educator (aka the expert) to fill them up with knowledge and skills. In BC, we are encouraged to hold an image of children as capable, competent, and full of potential and strengths. To support students in their early explorations of this ‘Image of the Child’ I ask them to consider their own childhoods – how they felt they were viewed and responded to – and how this empowered them, left them disengaged, or somewhere in-between. I ask them to consider their own values and beliefs – and then rationalize their view of children (and their practice as Educators) based on those values. In the past, I hadn’t really viewed it as ‘sticking’ this to prior knowledge – it was really just about personalizing and then getting really clear about the path from values to practice. However, the first chapter in the book has given me a new (and really useful) frame of reference for how to approach this discussion with students!

I initially struggled to identify what my own expectations (re: prior knowledge) were for students coming in to an introductory course – not sure if others did too? I knew I didn’t expect them to hold knowledge of developmental theories/theorists or types/areas of development. …but I knew I had expectations. Eventually the lightbulb went off and I realized the prior knowledge I expected them to have was their own experiences with childhood and what influenced it. It sounds so simple now – but amazing how complex that felt.

Hi Alib26,

What you said is so interesting. HLW authors define prior knowledge (PK) much more broadly than I had originally thought of it …as including “knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes gained in other courses and daily life”. (p.4) Learning is “hindered” when the PK is incorrect (Jennifer’s Physics example), but it’s a bit more involved to uncover learner *attitudes* about the subject (Sybill on Emergency Management; Isabeau on Faculty and Active Learning) as well as, understanding their *beliefs* about the nature of the subject or what pre-conceptions they might have on their abilities to learn that subject (Becky on Writing; Janine on Ed Tech).

Before starting this book club, I thought about my own expectations of what prior knowledge I’d expect participants to have (about teaching and learning, or specifically, prior knowledge on prior knowledge :)). I’m still thinking on that. This is one of the challenges of an open learning opportunity…I think I’ve been thinking less so on what PK the participants might have on the subject (such as being well-versed in learning theory or cognitive psychology, etc.) , but more on the attitude of openness to learning together and willingess to share in this new book club format we are trying out. I’d be curious to know how others would view how we should be considering PK in our book club.

I think some of my English students hold the misconception that learning is a passive activity where knowledge is transmitted from an “expert” to the student. It is sometimes difficult to establish ‘buy in’ that students need to be actively engaged in (co)constructing their learning experiences. In my course, students are expected to read literature outside of the classroom and come in ready to engage creatively and collaboratively with their classmates using.

I have tried strategies such as being explicit about the classroom format, teambuilding, goal setting, self assessment, providing response choices, assigning grades to in-class participation activities, etc. I think as I get more comfortable with my own style of teaching, it gets better and more authentic.

I would love to hear ideas from others about how to encourage students to get involved in their learning — especially if your course is a requirement rather than a passion or an interest.

I teach art history. After a few weeks of class, in order to get a sense of how far the class has come in their understanding of particular art movements, we do an index card exercise. I hand out a bunch of cards. They might say “art of noise” or “chocolates and champagne” or “two mountain climbers roped together” and the students have to work in groups and make decisions, get up, move around the room, and put the cards into thematic blocks. There is a lot of card switching as more cards are added and people change their minds. For the examples above, it might take awhile for the students to connect art of noise to Futurism or chocolates and champagne to Rococo art, or two mountain climbers roped together to Picasso and Braque’s collaboration in developing Cubism, but they enjoy the challenge. At the end of the exercise a lot of them will take photos of the thematic categories and use them for study purposes. After a few more weeks, we might have another index card exercise – it makes visible how many concepts they are adding to their visual tool kit.

Hi Englishgirl0160,

Your post brought to mind the work of Robin de Rosa and how she engaged her students by having them put together their own textbook. http://robinderosa.net/uncategorized/my-open-textbook-pedagogy-and-practice/ If you haven’t heard her speak there is an inspiring video recording of a talk she did here in Vancouver. : https://stream.langara.ca/media/t/0_lktrverk

After reading chapter 1, I am inspired and a little perplexed. For the inspired part, I really appreciated some of the suggestions around ‘activating’ prior knowledge. Right now, I’m co-facilitating a ‘Course Design’ course for college Instructors and we are using concept mapping to help the Instructors to think about the content they would like to include in their course and to visually explore prioritizing and organizing (connecting) content. I liked the suggestion of using concept maps over time (perhaps at the beginning and the end of a course) to show how learning (and perhaps priorities and organizational thinking) can change over time.

As for the perplexed part, I am struggling with the language of “inaccurate” and “inappropriate” to describe prior knowledge. While I agree, there are ideas and principles that have stood the test of time, I also strongly believe that Western knowledge (in particular) is continually evolving and changing, in some areas, and many strongly held ‘scientific’ beliefs have drastically changed over time (i.e. the medical and societal belief that women and indigenous people are mentally inferior). Along the same lines, I have been in engaging and challenging course discussions around Western vs. Indigenous classifications of ‘animate’ vs. ‘inanimate’ (of trees and rocks etc.). As such, I think we have to be cautious and thoughtful in how we classify prior knowledge and really be aware of the ‘multiple ways of knowing’ that can both challenge and enrich our classrooms.

Thank you for your participation today Polly. Could we share your link for your blog here?

Hi Leva,

The blog post I referred to is the one above under PDMADSEN (Sept. 14).

Thanks for your facilitation!

Polly

It was great to meet you today!

Hi Polly,

Ok thank you. I was thinking you had a separate blog.

During our discussion, we did reflect on your post – on being aware that there are different ways of knowing based on different PK/perspectives/beliefs and that some knowledge may change over time. And that the challenge is that it’s not always simple.

Thanks you for participating. This week will be great – hope you can join us.

I really appreciate your comment. It provides a reminder that while we should be aware of when prior knowledge is acting as a barrier or a source of misunderstanding in the current learning environment, the way in which we respond to it–even in our own thinking which we often unconsciously reveal to our students–needs to be free of judgment.

First of all, I would like to say that I am thrilled to be part of this book club and look forward to conversing with you all and sharing ideas with you. I teach in a Health Care Assistant program where the goal is to provide learners with both the theoretical and hands-on knowledge necessary to provide care to patients. The beauty of this short vocational program is that people from all walks of life enter my classroom. Some have prior knowledge from nursing in other countries and many have prior knowledge from previous careers. Really, a one-size-fits-all approach in my teaching and delivery tends not to be successful. In my teaching practice I try to get to know each individual and draw out their experiences and strengths as they go through the learning journey. Some students have recently come from high school and some of my students have been away from the classroom for thirty years or more.

On p.3 of our book, Ambrose et al. (2010) note that “learning is a process, not a product”. Sometimes the learners I work with think that the process is complete when they graduate and start working. As a teacher, I can help promote lifelong learning and have the learners leave my classroom knowing that they will continue learning and they are the ones in charge of this over the course of their lives (Ambrose, 2010). I have appreciated and enjoyed the responses so far this week and am looking forward to getting to know all of you a little better.

Daina Moore

Capilano University

Hi Daina,

We are pleased to have you join us too! Thanks for your views about “lifelong learning” and learning as a process and a journey. It brings to mind some of the awareness being made now about the need to teach the “whole student” and consider all they bring to the learning experience their “prior knowledge” beyond the knowledge of the subject matter. You might find of interest some of the work Douglas College is doing with their faculty and staff on “teaching the whole student” https://bccampus.ca/2017/01/24/storming-the-ivory-tower-a-workshop-on-transforming-post-secondary-education/

Best,

L

Really wonderful reflections from everyone. Thank you, Looking forward to Chapter Two!

The winner of the Chapter One prize draw is Sandra Seekins. We’ll be sending you your Chapters-Indigo card this week. Congrats and enjoy.